The Barcelona Chair needs little in the way of introduction. One of the most iconic and celebrated designs of the 20th century, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Chair appears to us now “as if it has existed forever,” according to Michael Jefferson, Senior Vice President of Wright, the auction house. Jefferson has overseen Mies’ furniture at auction for decades, and is an authority on the chair’s design, production and manufacture.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Barcelona Chair as manufactured by Knoll. Image from the Knoll Archive.

In the first of our series Design Deconstructed, Knoll revisits this landmark design from Knoll’s catalog to trace its evolution from initial concept to coveted collectible. Intended as a resource for customers and collectors alike, this timeline—assembled with the help, cooperation and expertise of Michael Jefferson—charts the major developments associated with Mies’ most well-known furniture design: the Barcelona Chair.

1928: Sketches

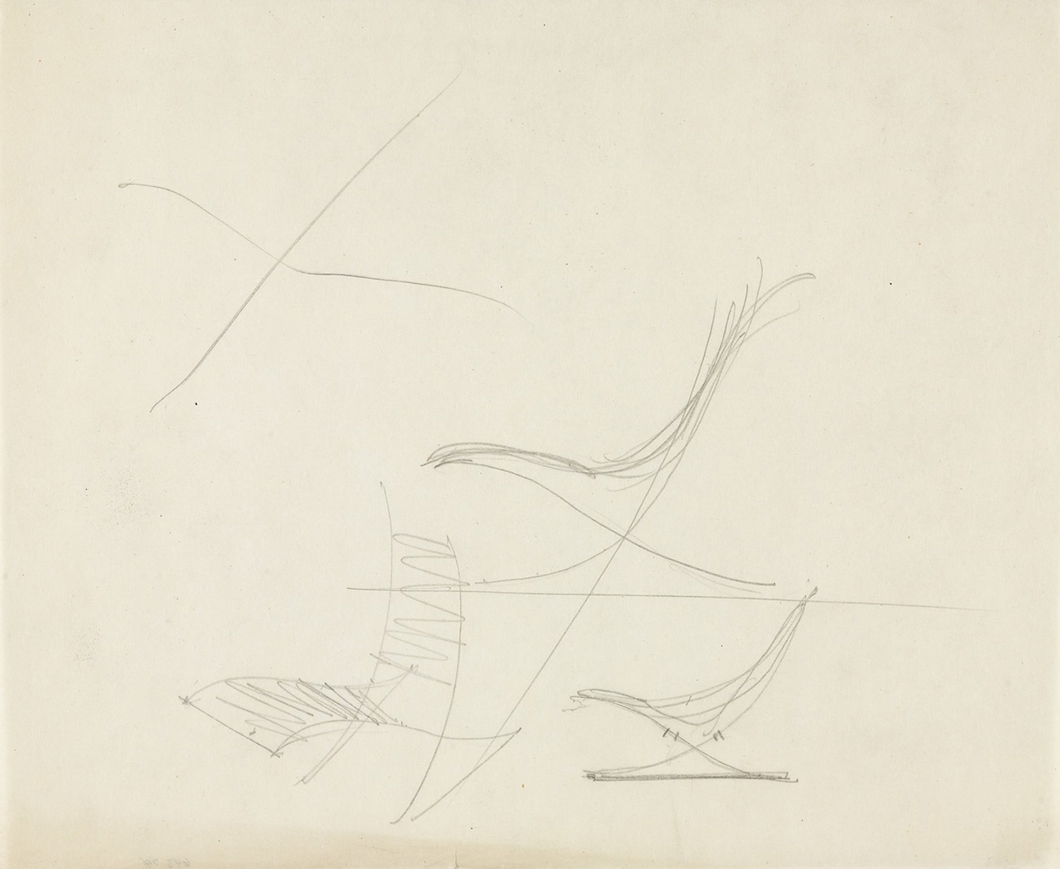

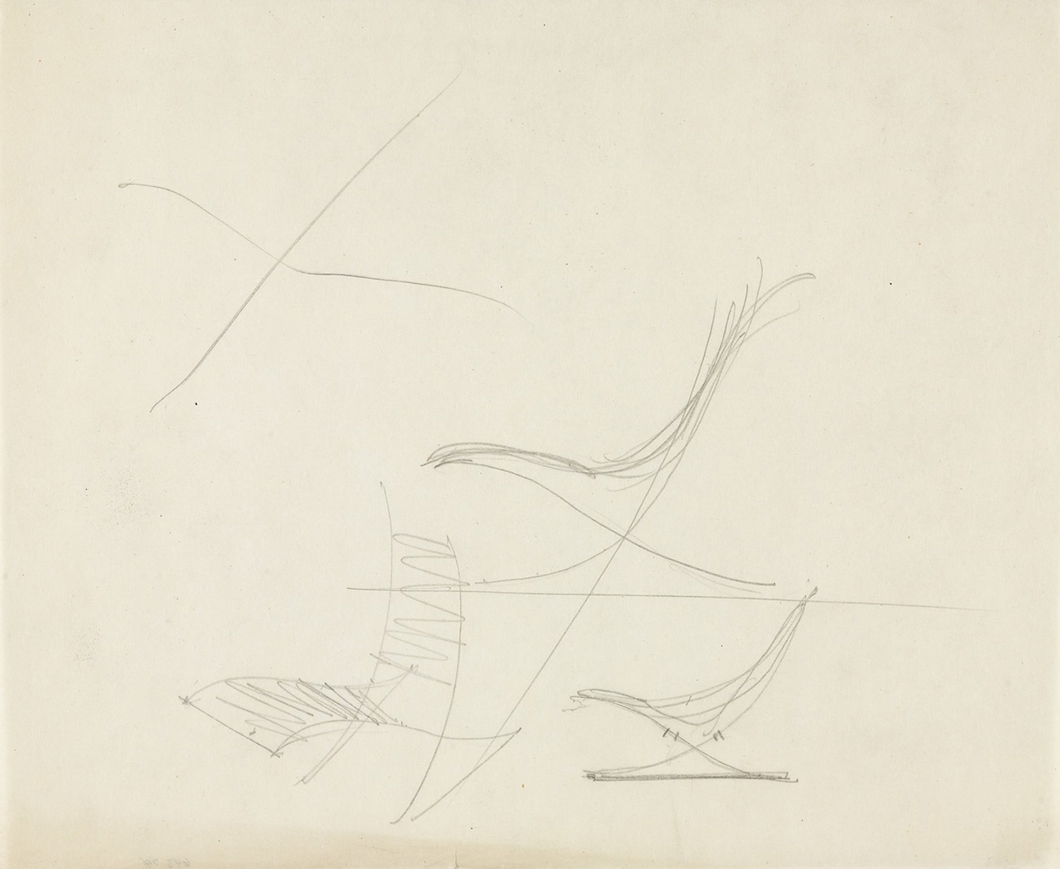

"Lounge Chair Without Arms" c. 1926-1946. Image courtesy of The Architecture & Design Study Center, The Museum of Modern Art.

In 1928, sketches for the Barcelona Chair first appear alongside other seating solutions Mies was experimenting with at the time. Inspired by classical forms, the Barcelona Chair’s basic, scissor-shape design (known as a curule seat) dates back to 1500 BC. A reprised form, examples of the curule seat have been found in Egyptian, Greek and Roman designs throughout history, often with strong connections to seats of power.

“As opposed to earlier precedents, the Barcelona Chair places the axis at the sides, producing a highly cantilevered seat.”

—Michael Jefferson

Karl Friedrich Schinkel's Cast-Iron Garden Chair, 1825. Image courtesy of Vitra Design Museum.

The most direct precedent for the Barcelona Chair arrived in the form of Karl Friedrich Schinkel's cast-iron garden chair. Seen now as a harbinger of modernism, the 1825 design was among the first to utilize the cast-iron process to produce furniture efficiently on a large-scale. Each identical side piece was forged as an entire unit, offering great stability with minimum materials.

Although influenced by Schinkel, Mies’ interpretation of the curule form merits its own special consideration. “As opposed to earlier precedents, where the axis is found at the front to rear elevations of the chair,” Jefferson explains, “the Barcelona Chair places the axis at the sides, producing a highly cantilevered seat, that really became possible only in the contemporary period with modern materials.” The result was an unadorned chair of “pure structure,” representing the perfect marriage of form and function.

1929: Barcelona Pavilion

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Barcelona Pavilion, 1929. Image courtesy of The Architecture & Design Study Center, The Museum of Modern Art.

Originally made for display, only two iterations of the Barcelona Chair were specifically designed for the Barcelona Pavilion. Through their incorporation, “Mies sought a formal a solution to accompany the free-standing walls and planes of the Barcelona Pavilion,” intended to symbolize the new progressive spirit of the Weimar Republic. Mies said that the design had to be more than a chair, but “a monumental object.” As organizational elements, the chairs and accompanying ottomans were positioned throughout the pavilion as fixed pieces—Mies intended for them to remain in place.

Aware that King Alfonso XIII would be in attendance, Mies also famously said that the Barcelona Chair would be "fit for a king," giving way to the misconception Barcelona Chair was designed as a monarchic object—an idea since largely discredited by scholars.

“I’m not sure there’s a more singular expression of Mies’ aesthetic and rigor than the Barcelona Chair.”

—Michael Jefferson

A Knoll-produced replica of the original Barcelona Chair, presented as a gift to MoMA in 1953. Image courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art.

The two original models had a bolted, chrome-plated construction with ivory-colored pigskin cushions. In 1953, Knoll created a replica of one of the ivory-colored chairs and presented it as a gift to The Museum of Modern Art.

1930: Philip Johnson's Southgate Residence

Philip Johnson's Southgate Residence. Image courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art.

In 1930, Philip Johnson—who met Mies in 1928, when he was working on the Barcelona Pavilion—granted Mies his first U.S. commission. Johnson had returned from an extended trip to Europe as a proselytizer of the new International Style, and accordingly tasked Mies and Lilly Reich with designing his Southgate residence at 424 East 52nd Street.

The residence was the first to utilize Bauhaus concepts and introduced the Barcelona Chair to America. Johnson went on to use his Mies-designed furniture in subsequent New York apartments, which he designed himself.

1930: Josef Müller

The first commercial production of the Barcelona Chair followed shortly after the debut of the Barcelona Pavilion. The chairs were made by hand out of the Berliner Metallgewerbe studio of Josef Müller in Berlin.

1931: Bamburg Company

“It was Mies’ affinity for the timeless and preference for the permanent that is responsible for the chair we instantly recognize as the Barcelona Chair.”

—Michael Jefferson

The Barcelona Chair c. 1931, produced by the Bamburg Company. Image courtesy of Wright.

One year later, the chair appeared in the 1931 product catalog of the Bamburg Company, signaling the first attempt to mass produce the chair. Chrome plating was a new process in furniture design, and the company lacked sufficiently large vats to plate the one-square-meter welded frame. As a result, components were bolted and lap jointed, with two screws placed on a diagonal. These early iterations of the chair featured horsehair-filled cushions, like those originally designed for the Barcelona Pavilion.

The Barcelona Chair c. 1931, produced by the Bamburg Company. Image courtesy of Wright.

1931-1932: Design Improvements

“Mies pursued the scissor-shape because of it had inherent structural stability, an integrity, what he called ‘an air transparency.’”

—Michael Jefferson

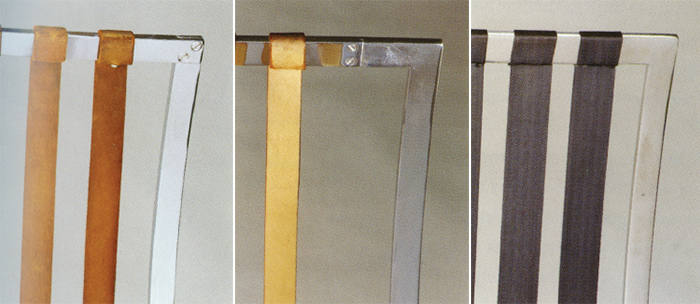

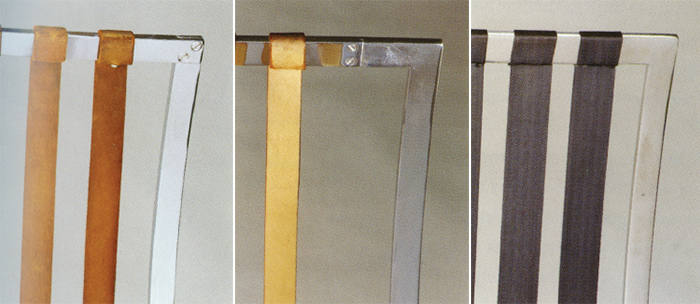

Improvements to the Barcelona Chair c. 1931-1932, as implemented by the Bamburg Company. Images courtesy of Wright.

With Mies’ consent, the Bamburg Company began to make select improvements to the design. After observing deterioration at the joints, the point of connection migrated inward, increasing the stability and durability of the design. By 1932, the intersecting joint had been hidden underneath the chair’s leather straps, affording the design a seamless appearance.

1932-1934: Thonet

The Barcelona Chair c. 1932-1934, as produced by Thonet. Image courtesy of Wright.

In 1932, production passed to Thonet, who continued to produce the chair for only two years, until events leading up to the outbreak of WWII halted production. By 1938, Mies van der Rohe had fled Germany, relocated to Chicago and become the director of Illinois Institute of Technology.

1945: Florence & Mies

“Almost all the really significant, early innovations in modern furniture design were carried out by architects, like Mies van der Rohe.”

—Florence Knoll

Florence Knoll as a student at Cranbrook Academy. Image from the Knoll Archive.

While at IIT, Mies was approached by former student Florence Knoll with the idea to produce Mies’ entire collection of furniture en masse for American and international markets. As an early mentor and tutor to Florence, Mies decided to grant Knoll, Inc. with the rights to manufacture the design.

The company's initial attempts to prototype the design included experiments with aluminum, but the material change brought with it a whole host of problems. Knoll decided to scrap aluminum in favor of chrome-plating.

1945-1947: Titlegratz

The Barcelona Collection at Philip Johnson's Glass House, 1949. Image from the Knoll Archive.

During the interim period between 1945 and 1947, production of the Barcelona Chair continued in New York, where it was manufactured by Titlegratz. Select examples from this period crop up in various Philip Johnson interiors.

1947: Knoll

“In 1929, Mies van der Rohe designed the Barcelona Chair. See it at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, and buy it through Knoll Showrooms in 28 countries.”

—Advertisement c. 1947

An advertisement announced the arrival of the Barcelona Chair to the Knoll product catalog in 1947. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Knoll production began in 1947. Manufactured out of the company’s factory in East Greenville, Pennsylvania, these early models are chrome-plated, tufted on one side and feature a flat piece of leather on the chair's back. The most distinctive feature of a Knoll-manufactured Barcelona Chair is the thick welted piping seen on the cushions, stuffed with a dense industrial foam. Original upholstery tags also certify Knoll manufacturing.

1960: Jerry Griffith

The Barcelona Chair as manufactured by Jerry Griffith, c. 1960. Image courtesy of Wright.

Examples of Chicago-produced Barcelona Chair began to appear in 1960. Manufactured by the metal-worker Jerry Griffith, this iteration of the Barcelona Chair was the first to utilize stainless-steel. Griffith’s design sacrifices an element of long-term durability for elegance in its distinctive cross-joint, notable for the lack of extra supportive welding material. This design was utilized in many Mies-designed buildings in Chicago, including 886 North Shore Drive.

1964: Shift To Steel

“Each material has its specific characteristics which we must understand if we want to use it. This is no less true of steel.”

—Mies van der Rohe

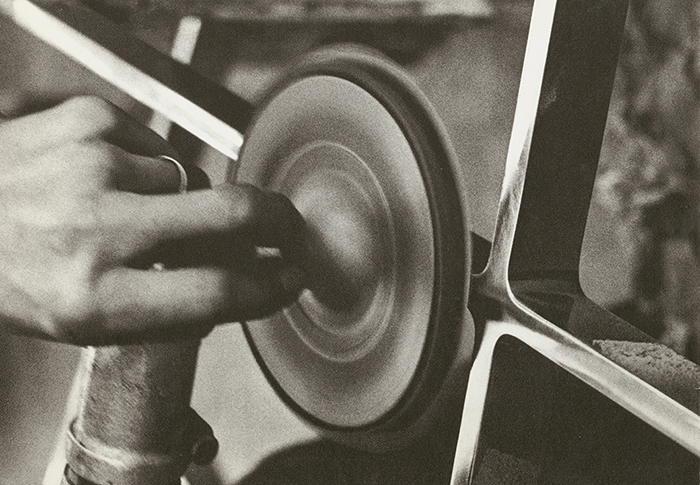

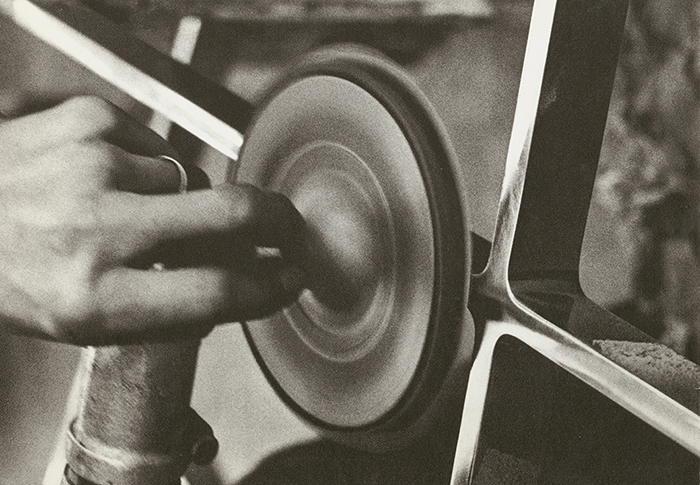

The Barcelona Chair in production at the Knoll factory in East Greenville, Pennsylvania. Image from the Knoll Archive.

Following Griffith’s lead, in 1964 Knoll production shifted to stainless-steel. Mies proclaimed that he would have utilized stainless steel from the beginning had the technology been available to him.

1970s: Bronze

The Barcelona Chair in bronze c. 1970s. Image courtesy of Wright.

After Mies death in 1969, Knoll began manufacturing bronze-plated versions of the Barcelona Chair for special commissions, particularly in the Midwest. Jefferson recalled, “I spoke with Bobby Cadwallader, the former director of Knoll, and he said, ‘I don't know what it is about Chicagoans, but they seemed to order en masse these bronze-plated Barcelona Chairs.‘”

1990s: Mies’ Signature Added

“Like any great design, there is a temptation to copy it, [and] this is rampant with the Barcelona Chair.”

—Michael Jefferson

KnollStudio Mies van der Rohe signature on the Barcelona Chair. Image from the Knoll Archive.

“Like any great design,” Jefferson stated, “there is a temptation to copy it, [and] this is rampant with the Barcelona Chair.” In the mid-90s, KnollStudio added Mies’ signature to the back right leg of the Barcelona Chair to further differentiate the design from the many derivative versions in the marketplace.

2004: Mies Protected

The Barcelona Collection as manufactured by Knoll. Image from the Knoll Archive.

After a drawn out process, Knoll successfully obtained a federal trade dress protection for five pieces designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, including the Barcelona Chair and Ottoman, in 2004. Trade dress protects the “total visual image” of a product, affording the recipient with stewardship of the product in the marketplace. The measure has been essential to protecting Mies’ designs from inelegant, unauthorized copying.

All images are courtesy of the Knoll Archive unless otherwise noted.

This timeline is based on Michael Jefferson's presentation A Brief History of the Barcelona Chair & Mies' Furniture at Auction which he first delivered on March 28, 2011 at The Mies van der Rohe Society. It has been adapted with his explicit permission.